The Mycelial Sensing of Networks

Toward Ecological Organization

This short essay draws on the work of many peers, in particular Austin Wade Smith, Jeff Emmett, Scott Morris, Jessica Zartler, Michael Zargham, Sheri Herndon, Patricia Parkinson, Richard Flyer, Kevin Owocki, Ferananda Ibarra and Christina Bowen.

Introduction: The Network Already Around Us

We exist, each of us, as nodes within vast constellations of relationship. This isn’t a metaphor but a practical reality. As a parent navigating after-school programs, as a member of a neighborhood association or community garden, as a participant in reading circles, religious institutions, activist groups, or professional communities, we are already embedded in networks that contextualize and give meaning to our lives. These patterns of connection are not novel; they are ancient, mirroring the fundamental architecture of living systems themselves.

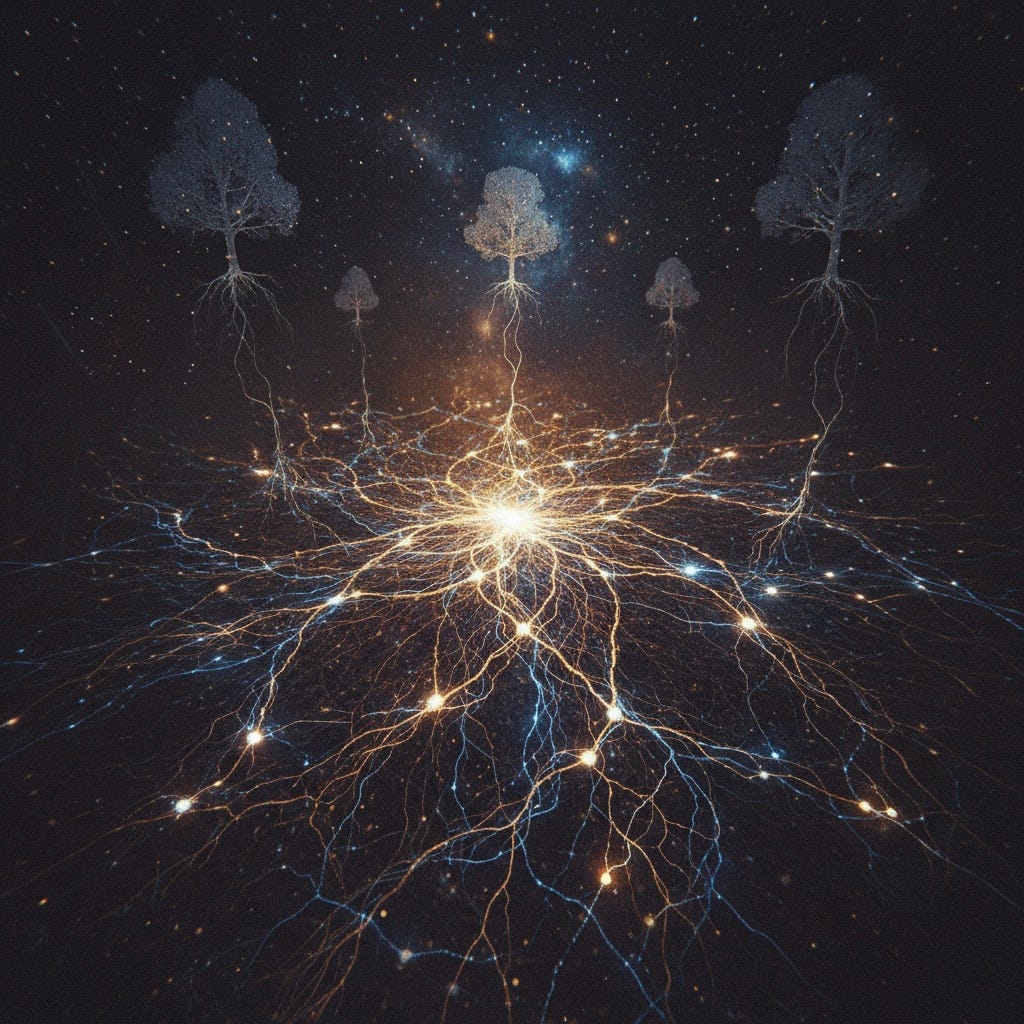

The natural world demonstrates this architecture with elegant clarity. Ecosystems function as living wholes, with information, resources, and energy flowing through networks that sustain the macroorganism of the ecology itself. The mycelial networks beneath forest floors, the neural pathways of organisms, the food webs that bind predator to prey to decomposer, all operate through distributed intelligence rather than centralized command. Networks, in this sense, are both ancestral and emergent, both the foundation of life itself and a newly formalized mode of human organization that we are only beginning to understand.

Yet for much of recent history, particularly within the context of modern institutions, we have operated within organizational forms that contradict this networked reality. These forms, hierarchical, enclosed, extractive, function as parasites upon the networks they inevitably depend upon, even as they deny or obscure those dependencies.

The Enclosure of Organization

The dominant organizational paradigm of modernity is one of enclosure. A small executive group sits at the apex: a board, a C-suite, a leadership team. This configuration concentrates decision-making authority within a circumscribed circle, while broader constituencies exist primarily to enact decisions made elsewhere. This is not merely an administrative arrangement; it is the structural manifestation of a worldview premised on centralized authority and hierarchical control.

This organizational mode correlates directly with epistemologies of power that position some as inherent decision-makers and others as executors, some as strategists and others as hands. It creates artificial boundaries between entities that might otherwise collaborate, encourages competitive rather than cooperative dynamics, and generates the fragmentation that characterizes so much of contemporary organizational life. Projects become siloed. Organizations duplicate efforts unknowingly or compete unnecessarily. The larger ecology within which all these efforts exist becomes invisible, and with that invisibility comes profound inefficiency and missed potential for synergy.

Through the lens of ecological consciousness, each being is an agent, a node in the network with their own perspectives, needs, and agency. What makes our current organizational paradigm particularly tragic is that it actively and ongoingly denigrates the sacredness of this underlying embeddedness, relationality, and agency. The relationships, the overlapping memberships, the shared values and adjacent missions are all made invisible by hierarchical and enclosed structures. When we fail to organize ecologically, we dishonor and fail to leverage the web of agency within which we already exist.

Networks as Organizational Form

To understand networks as an organizational form is to propose something both radically different and intuitively familiar. Networks formalize the relationships that already bind us, making explicit what has been implicit. In doing so, they create infrastructure for self-organization, the process by which agents within a system, recognizing their own agency, choose to align their efforts toward shared purposes without requiring centralized command.

This process cannot be rushed or manipulated without losing integrity. It is fundamentally relational, proceeding at the pace of trust-building and genuine understanding. It requires deep listening: the cultivation of awareness regarding how our particular gifts, capacities, and purposes relate to the larger whole. This is not a skillset most of us arrive with fully formed. It must be studied, practiced, learned through doing.

I do not claim expertise in this domain but rather approach this field as an active student and practitioner. My work, both globally through OpenCivics with Patricia Parkinson, and locally through the Regen Hub I helped cofound in Boulder, as well as various networks of community organizers and leaders, constitutes an active learning laboratory. In each context, the central challenge remains consistent: how to make the network and the connectivity between projects more explicit, so that collaboration becomes more seamless and coherent.

The answer, I am increasingly convinced, lies in understanding our differentiation within a fundamentally ecological context.

Ecological Differentiation: Finding Our Role in the Whole

Conventional organizational thinking operates from a framework of isolation. Each entity sees itself as separate, complete unto itself, in competition with others for resources, attention, and legitimacy. Even when organizational missions align, this fragmentation persists. We find ourselves either attempting to do everything, to be comprehensive in ways that exhaust resources and dilute impact, or focusing so narrowly that we lose sight of how our work connects to the broader ecosystem of efforts surrounding us.

Ecological thinking offers a different framework. Instead of isolated entities, we begin to perceive the web of relationships and the larger ecology within which our community, network, group, or organization is situated. This shift in perception, from fragmented to ecological, opens up entirely new possibilities for coordination and collaboration.

As we become aware of the social ecology of different people, projects, and initiatives, we can start to understand how to work within networks rather than against them. We can identify not only what we uniquely contribute but also what others contribute, how those contributions complement rather than compete with our own, and where opportunities for alignment and mutual support exist.

This is not a process of homogenization. Nature demonstrates abundant room for redundancy. Multiple species may occupy similar niches within an ecosystem, and this redundancy creates resilience. The goal is not to eliminate overlap or to designate “winners” who monopolize particular functions. Rather, it is to understand affiliations and domains such that, even when playing similar functions, we approach our work non-rivalrously. We align in how we share knowledge and resources, recognizing ourselves as fundamentally part of the same ecology.

The Mycelial Sensing Process

This brings us to the mycelial sensing of networks, the intuitive, relational process of discovering how initiatives and organizations can best relate to one another within a larger ecological context.

One of the most powerful aspects of networks is discovery. In graph theory terms, networks consist of nodes (entities) connected by edges (relationships). As we begin to see technological representations of these networks, layered, interconnected, visualized, we gain the capacity to explore possibilities for collaboration from a fundamentally relational orientation. We can perceive networks of trust, networks of affiliated projects, overlapping memberships, and shared values. Simply making these visible catalyzes something important: it becomes easier for groups to identify their unique differentiation within the ecology.

This process resembles the function of mycelial networks in forest ecosystems. Beneath the visible world of individual trees exists a vast fungal network that connects root systems, facilitating the exchange of nutrients, water, and information. Trees that appear separate are in fact deeply interconnected, supporting one another through this hidden infrastructure. Mother trees nurture saplings. Struggling trees receive resources from their neighbors. The forest operates as a superorganism, with the mycelial network serving as its nervous system.

Human networks, when allowed to function ecologically, demonstrate similar patterns. The mycelial sensing process involves the intuitive navigation of relationships, the recognition of complementarities and adjacencies, the pruning of redundant efforts not through competition but through collaborative discernment about what each entity can uniquely contribute.

This might mean that one organization focuses primarily on convening, another on resourcing, another on specific programmatic interventions. What matters is not rigid differentiation but the recognition that all exist as part of the same network, that the space between organizations is not empty but alive with possibility for connection and mutual support.

Formalizing Networks: From Invisible to Visible

Formalizing networks, making them visible and explicit, serves multiple essential functions.

First, it enables better information flow. When organizations understand themselves as nodes within a network, they can share knowledge more intelligently, avoiding duplication while building on each other’s learning. Information becomes a resource that circulates through the system rather than remaining trapped within organizational silos.

Second, formalization enables coordinated resource attraction. Rather than competing for the same limited pool of funding, networked organizations can present themselves as a synergistic portfolio. They can make the case to funders that supporting the network represents investment in an entire ecosystem rather than isolated projects. This fundamentally changes the value proposition: funders are not betting on individual winners but nurturing the conditions for emergence across an interconnected system.

Third, visibility allows for better role clarity and reduces wasteful redundancy. This is not about eliminating all overlap, again, redundancy can be valuable, but about ensuring that when similar functions exist, they are coordinated rather than competing, aligned in purpose rather than working at cross-purposes.

Network Formation in Practice: Bioregional and Digital Examples

This process of network formation is currently underway in multiple contexts, both digital and bioregional.

In the online sphere, we see the emergence of Network Nations, communities organized around shared values, purposes, or identities that transcend geographic boundaries. These digital networks enable global affiliations and alignments, allowing people to organize around shared commitments regardless of physical location.

Simultaneously, we are witnessing the formation of bioregional networks rooted in geographic proximity and shared environmental context. I observe this happening in Cascadia in the Pacific North West, on the Front Range of Colorado, and emerging to some extent in the Northeast and the Bay Area. These bioregional networks recognize that certain challenges and opportunities are intrinsically tied to place, and that collaboration among geographically proximate actors can generate unique forms of synergy.

Here in Boulder, on the Front Range, I see many organizations playing unique roles while only beginning to recognize themselves as a network. The process underway involves identifying what exists in the space between our different organizations and efforts, what network-level functions might need support, what shared infrastructure might benefit the whole, what forms of coordination might unlock new possibilities.

This is fundamentally a process of intuitive sensing: how do our initiatives relate to each other? What is the right relationship between our organizations? This might involve recalibrating expectations about what we can uniquely contribute, releasing certain functions that others are better positioned to serve, while claiming more fully those capacities that represent our genuine differentiation.

The result is not a static division of labor but a living ecology of relationships that can adapt as conditions change, as new actors emerge, as new needs become apparent.

Upward Spirals: The Promise of Networked Organization

When networks function well, when the mycelial sensing process is allowed to unfold with integrity, they create upward spirals. By knowing our unique gifts and our role in the larger ecology, we generate conditions for holism: the whole becomes exponentially greater than the sum of its parts.

This is more than rhetorical flourish. In concrete terms, it means that networked organizations amplify each other’s impact. A convening by one organization generates insights that inform programming by another. Resources flow to where they can be most effectively deployed. Redundant efforts are minimized not through competition but through coordination. New actors entering the system can more quickly find their place and their people. The entire ecosystem becomes more intelligent, more resilient, more capable.

This is the promise of networks: not merely improved efficiency (though that often follows) but the emergence of collective intelligence and capability that exceeds what any individual organization could achieve in isolation.

Conclusion: Learning to Sense the Mycelium

We are, all of us, already embedded in networks. The question is not whether to participate in networks but whether to participate consciously, whether to make visible and formal the relationships that already constitute the living tissue of our communities, our movements, our shared work.

Learning to sense the mycelium is an ongoing practice. It requires cultivating awareness of the ecological context within which we operate. It demands the humility to recognize that our organization or project is not the center but one node among many. It asks us to develop comfort with emergence, with self-organization, with forms of coordination that cannot be controlled from the top down.

This is challenging work, particularly for those of us trained in conventional organizational paradigms. It asks us to trust in processes that feel less certain, more organic, more dependent on relationship than on formal authority. It requires patience with the pace at which genuine trust and alignment develop.

Yet the alternative, remaining within parasitic organizational forms that deny the networked reality we already inhabit, becomes increasingly untenable. The challenges we face, from climate disruption to social fragmentation to economic inequality, are systemic in nature. They cannot be addressed through isolated interventions but require the coordinated intelligence of networks.

The mycelial sensing of networks is not a technique to be mastered but an orientation to cultivate: an ongoing attentiveness to relationship, to complementarity, to the larger ecology within which we are always already embedded. As we develop this capacity, individually and collectively, we participate in the emergence of organizational forms adequate to the complexity and interconnection of our time.

The network is already here. Our work is to see it, to formalize it, to tend it with the care it requires. In doing so, we may discover that we are not building something new but rather remembering something ancient: the fundamental pattern of life itself, expressed now through conscious human-ecological organization.

Hi Benjamin. Fascinated by the topic of how organizations can learn from nature. Read your article with excitement. I am exploring the topic now through the fluidity of water. How do we as orgs and individuals recover the inherent fluidity. Would be curious if you have any thoughts on this. Here are some of mine https://open.substack.com/pub/yuliabogdanova/p/teach-me-about-fluidity-water-part?r=18luu7&utm_medium=ios

Wonderful read and beautifully written.

Thank you 🙏