Collapse, Parallel Societies, and the Bioregional Imperative

Place-Based Solidarity in the Age of Unraveling

The Unraveling Social Contract

We live in an era of profound institutional failure. The social contract that once bound citizens to states through mutual obligation has been systematically dismantled over decades of neoliberal extraction. Where states once provided security, infrastructure, and collective purpose in exchange for taxation and civic participation, we now witness the wholesale abandonment of public responsibility. Healthcare becomes a luxury good. Education transforms into debt bondage. Housing evolves from human right to speculative asset. The very notion of public good has been privatized, leaving citizens as consumers in a marketplace where survival itself requires capital most cannot access.

This dissolution accelerates through cascading feedback loops. Climate chaos overwhelms infrastructure designed for a stable world. Supply chains optimized for efficiency shatter at the first disruption. Democratic institutions, captured by corporate interests, lose legitimacy as they fail to address existential threats. The meta-crisis — Daniel Schmachtenberger's term for our interconnected catastrophes — reveals not isolated failures but systemic breakdown. Each crisis amplifies others: ecological collapse drives migration which destabilizes politics which prevents climate action which accelerates collapse.

The response from existing institutions has been either denial or acceleration. States double down on border militarization rather than addressing root causes. Corporations extract what remains while building private bunkers. The wealthy construct enclosed parallel systems — private firefighters, personal medical concierges, gated archipelagos — while public services wither. We are witnessing not just inequality but the emergence of parallel civilizations: one with access to functioning systems, another abandoned to entropy.

The Collapse-Aware Spectrum

Against this backdrop, a growing movement of collapse-aware communities has emerged. These range from the Doomer subcultures who have simply opted out — withdrawing into nihilistic acceptance or individual preparation — to sophisticated networks attempting to build alternatives. The spectrum is vast: preppers stockpiling ammunition, ecovillages creating autonomous zones, transition towns relocalizing economies, and bioregional movements rebuilding from the ground up.

The Doomers represent one pole of collapse awareness: recognition without agency. Having internalized the scope of civilizational failure, they retreat into various forms of withdrawal. Some become digital nomads, exploiting currency arbitrage while contributing nothing to local resilience. Others disappear into homesteads, focused on family survival while abandoning collective possibility. The Doomer represents ultimate atomization — each individual or family unit against the dying world.

Yet even among those who maintain hope for collective action, approaches diverge radically. The Network State movement, championed by Balaji Srinivasan, seeks exit through digital coordination and eventual territorial acquisition. These communities unite around ideological alignment—libertarian cities, Christian communes, techno-utopian enclaves — creating new forms of segregation based on belief rather than geography. They promise escape from failing systems through technological transcendence and selective association.

Meanwhile, indigenous movements and land defenders demonstrate another path entirely: doubling down on place-based resistance and regeneration. From the Wet'suwet'en protecting watersheds to the Zapatistas building autonomous municipalities, these movements understand that there is no exit from ecological reality. Their collapse awareness leads not to flight but to deeper rootedness, defending specific territories while building alternative governance grounded in ancestral knowledge.

Joe Brewer and the Bioregional Imperative

Of all the human beings who helped mid-wife me through my own collapse-awareness journey, Joe Brewer was not the first but he was among the most important. Joe is a larger than life figure whose personal journey embodies the evolution from global abstraction to place-based action. Trained as a complexity scientist studying existential risk, Joe spent years analyzing civilizational collapse. His intellectual understanding of collapse was vast and overwhelming. He teetered on the axis of his own reality. The tragedy of the ecological unraveling was extreme.

Joe’s transfiguration from a tragic to post-tragic figure would arrive through the birth of his daughter. An immanently sacred reality came pouring in through the cracks of collapse. Now, he had someone for whom he was bound by love to hold onto hope. And in that prayer for his own daughter, Joe re-discovered a new kind of active hope for humanity. Moving to Barichara, Colombia, he began working with local communities on watershed restoration and regenerative agriculture. This shift from analyzing global systems to healing specific landscapes reveals a crucial insight: regeneration cannot be abstract. It requires hands in soil, relationships with neighbors, and long-term commitment to particular places.

Through the Design School for Regenerating Earth, Joe now teaches what he learned through practice: bioregional regeneration requires more than ecological restoration. It demands cultural transformation, economic relocalization, and the patient work of rebuilding social fabric torn apart by centuries of colonialism and decades of neoliberalism. His evolution from systems theorist to bioregional practitioner illustrates a broader pattern among collapse-aware communities: the movement from abstract understanding to embodied response.

Joe’s work reveals that bioregionalism isn't merely an organizational strategy but an ontological shift. Rather than seeing land as property or resource, bioregional thinking recognizes landscapes as living systems of which humans are participating members. This requires a kind of "cultural prosthesis" — new cognitive and social tools that allow modern humans to perceive and respond to ecological complexity. The bioregion becomes teacher, showing through floods and droughts, abundance and scarcity, how human and natural systems interweave.

The Irreducibility of Place

Bioregional organizing emerges from a fundamental recognition: we cannot abstract ourselves from ecological reality. While digital networks enable coordination across distance, and ideological communities can unite dispersed populations, the material facts of existence — water, food, shelter, energy — remain stubbornly local. A watershed doesn't care about your political affiliation. Soil degradation affects everyone who depends on that land, regardless of their beliefs.

This irreducibility of place creates what we might call "forced solidarity." In a bioregion, the upstream forest manager and downstream farmer must coordinate regardless of their cultural differences. The conservative rancher and progressive permaculturist share an aquifer. The indigenous community maintaining traditional burns and the suburban development benefiting from fire protection exist in material interdependence. Place creates relationships that ideology cannot sever.

Yet this forced proximity alone doesn't generate coordination. Tragedy of the commons scenarios emerge precisely where people share resources without shared governance. What transforms mere coexistence into bioregional solidarity is the recognition of mutual fate — understanding that individual resilience depends on collective capacity. When your neighbor's ecological practices determine your water quality, their economic stability affects your security, and their knowledge might save your crops, solidarity becomes survival strategy.

This materialist foundation distinguishes bioregional networks from purely voluntary associations. You cannot simply exit a watershed when governance becomes difficult. You cannot fork a forest like a blockchain protocol. The physicality of place demands different organizational strategies — ones that accommodate irreducible diversity while enabling collective action. This is why bioregional movements must tend toward post-ideological frameworks, focusing on material needs and ecological health rather than shared beliefs.

Civic Culture and the Commons

The transition from atomized inhabitants to bioregional citizens requires profound cultural transformation. Centuries of enclosure — first of land, then of knowledge, finally of social relations themselves — have atrophied our capacity for collective stewardship. The civic muscles needed for commons governance have withered through disuse. Rebuilding them requires more than institutional design; it demands cultural practices that regenerate social fabric alongside ecological systems.

This civic culture emerges through what Peter Block calls "the structure of belonging" — regular practices that transform isolated individuals into interdependent communities. Shared meals become governance forums. Barn raisings teach collaborative construction. Seed swaps maintain agricultural biodiversity while weaving social networks. Time banks create reciprocal obligations outside market logic. Each practice builds what Robert Putnam termed "social capital" — the trust and relationships that enable collective action.

The commons, both physical and cultural, provide the medium through which this civic culture develops. Unlike private property (which individualizes) or state resources (which bureaucratize), commons require active participation in governance. Managing irrigation systems teaches water democracy. Maintaining tool libraries develops sharing protocols. Protecting forests requires conflict resolution between different use patterns. The commons become schools for citizenship, teaching through practice rather than theory.

Yet this civic culture cannot be imposed through top-down mandate or imported wholesale from other contexts. Each bioregion's culture emerges from its specific ecological patterns, history, and cultural inheritances. Salmon Nation's civic practices differ from those in the Sonoran Desert, shaped by different seasonal rhythms, resource constraints, and indigenous traditions. This place-specificity makes bioregional culture both deeply rooted and fundamentally plural—unified by commitment to place rather than homogeneous belief.

The breakdown of traditional institutions creates both crisis and opportunity for civic renewal. As states abandon rural regions and corporate supply chains prove fragile, communities must develop their own capacity for coordination. This forced self-reliance can catalyze civic renaissance — the return to mutual aid and collective stewardship that neoliberalism systematically destroyed. Yet it requires conscious cultivation. Without intentional practices that build trust and teach collaboration, collapse leads to warlordism rather than cooperation.

Cosmolocalism: The Bioregional Network Pattern

The bioregional movement embodies what Michel Bauwens calls "cosmolocalism" — a development pattern where knowledge flows globally while production stays local. This framework resolves a central tension in collapse-aware organizing: how to benefit from collective learning while maintaining place-based autonomy. Rather than either isolationist localism or rootless globalism, cosmolocalism enables planetary coordination without sacrificing bioregional specificity.

In practice, this means open-source designs for rocket stoves spread globally while each bioregion builds them from local materials. Governance innovations from Rojava inform watershed councils in Cascadia, adapted to different cultural contexts. The BioFi Project's economic protocols provide templates that bioregions modify for their specific needs. Knowledge becomes a commons flowing freely across boundaries, while implementation remains grounded in place.

This pattern enables what we might call "viral regeneration"—successful practices spreading through adaptation rather than replication. Unlike franchise models that impose standardization, bioregional networks share patterns that evolve through local application. Each implementation teaches something new, feeding back into the global knowledge commons. The result is not homogenization but differentiation—thousands of experiments in regenerative living, each suited to its specific context while contributing to collective understanding.

Digital infrastructure makes this cosmolocal coordination possible at unprecedented scale. Platforms like GitHub host governance templates anyone can fork and modify. Video calls connect bioregional practitioners across continents for knowledge exchange. Blockchain protocols enable resource sharing between bioregions without central intermediaries. Yet these tools serve bioregional ends rather than replacing place-based organization. Technology enables coordination but cannot substitute for the slow work of building relationships with land and neighbors.

The cosmolocal framework also reshapes economic relationships between bioregions. Rather than competing for mobile capital or racing to the bottom on environmental standards, bioregions can develop complementary specializations. Coastal regions might excel at kelp farming and ocean restoration while mountainous areas focus on forest management and watershed protection. Trade between bioregions could follow fair trade principles, ensuring value flows support regeneration rather than extraction.

The Dual Power Strategy

Bioregional networks operate through what Lenin called "dual power" — building parallel institutions while existing ones still function. Rather than revolutionary overthrow or patient reform, dual power creates alternatives that can both interface with current systems and survive their collapse. This strategy proves essential in our moment of institutional decay, where old systems fail but haven't yet disappeared.

The membrane institution model exemplifies this approach. Organizations like Regenerate Cascadia maintain legal nonprofit status, enabling them to receive grants, own property, and interface with government agencies. Yet they explicitly practice "institutional self-negation" — acknowledging their role as temporary scaffolding rather than permanent authority. They exist to facilitate network coordination, not to govern bioregions.

This dual structure allows bioregional networks to operate in the liminal space between functioning and failed states. They can access resources from existing institutions — grants, tax exemptions, legal protections — while building systems that don't depend on institutional continuity. When Pacific Gas & Electric fails to maintain rural infrastructure, local microgrids provide backup power. When federal disaster response proves inadequate, mutual aid networks activate immediately. When global supply chains break, local food systems provide resilience.

The sophistication of this approach cannot be understated. It requires simultaneously speaking the language of existing power — writing grants, filing paperwork, attending meetings—while building entirely different coordination mechanisms. It means maintaining legitimacy with systems you expect to fail while investing primary energy in alternatives. This psychological and practical complexity explains why many collapse-aware communities choose simpler strategies of exit or confrontation.

Yet dual power offers unique advantages in our extended moment of collapse. Unlike revolutionary movements that require decisive moments of rupture, dual power builds gradually through accumulation of capacity. Unlike reformist approaches that assume institutional continuity, it prepares for systemic failure. The strategy acknowledges that collapse is not an event but a process — one that might take decades to fully unfold.

Beyond Ideology: Post-Partisan Coordination

Perhaps the most radical aspect of bioregional organizing is its post-ideological character. In an era of escalating culture wars and political polarization, bioregional networks create coordination across difference. This isn't the false unity of "putting politics aside" but rather recognition that material interdependence transcends ideological division. The conservative rancher and anarchist permaculturist must collaborate on watershed management because they share the water.

This post-partisan approach emerges from necessity rather than principle. Bioregions contain irreducible diversity — different cultures, classes, political orientations, and relationships to land. Any attempt to impose ideological uniformity would fracture the networks needed for resilience. Instead, bioregional organizing focuses on material needs and ecological health — domains where shared interest becomes visible despite different worldviews.

The practice requires sophisticated facilitation and governance design. Sociocracy and consent-based decision-making allow groups to move forward without forcing agreement. Focus on specific, material projects — restoring a creek, creating a tool library, organizing fire protection — builds trust through shared work rather than shared belief. Over time, collaboration on practical matters can soften ideological boundaries, though difference remains.

This approach challenges both left and right political frameworks. It rejects the left's emphasis on ideological purity and reactionary dialectical consciousness, focusing instead on material interdependence and practical cooperation. It equally rejects the right's individualism and property absolutism, insisting on collective stewardship and mutual obligation. Bioregionalism represents something older than modern political categories the recognition that human communities are embedded in living systems that demand collaboration for survival.

The Question of Scale

Critics of bioregionalism often raise the question of scale. How can watershed-based organizing address global challenges like climate change or ocean acidification? How do bioregional networks coordinate beyond their boundaries? What happens when bioregional interests conflict? These questions reveal both limitations and possibilities within the bioregional framework.

The honest answer acknowledges that bioregional organizing alone cannot address planetary-scale challenges. No amount of local watershed restoration will stop Antarctic ice sheet collapse. No network of community forests can offset industrial emissions. Bioregionalism is necessary but insufficient—one strategy within broader transformation. It provides resilience and adaptation capacity for communities facing collapse, not prevention of collapse itself.

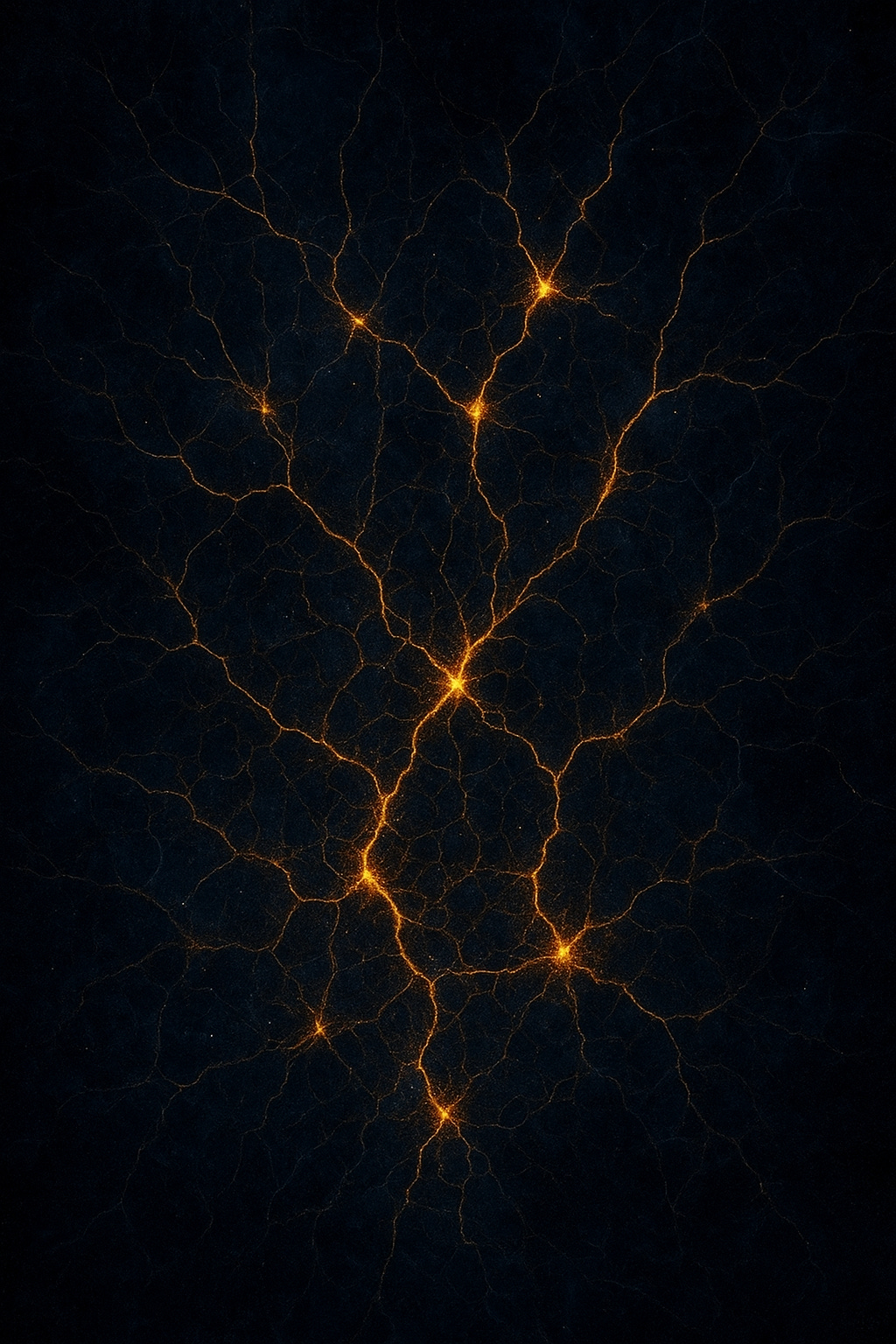

Yet bioregional networks demonstrate emergent properties at scale. When thousands of communities restore watersheds, cumulative impact becomes significant. When bioregions share knowledge and coordinate strategies, regional transformation becomes possible. The mycelial network metaphor proves apt—individual hyphae seem insignificant, but the network they create transfers nutrients across entire forests.

Inter-bioregional coordination remains underdeveloped but increasingly necessary. Climate refugees will move between bioregions. Watersheds cross multiple communities. Atmospheric rivers connect distant landscapes. These material relationships require coordination mechanisms that respect bioregional autonomy while enabling collective action. The cosmolocal framework provides one model, but others must emerge through practice.

Conclusion: Rebuilding from the Ground Up

The bioregional movement represents neither utopian vision nor dystopian retreat but pragmatic response to cascading systems failure. As nation-states prove incapable of addressing existential threats, as global capital cannibalizes the foundations of its own reproduction, as digital networks offer connection without community, bioregionalism provides a different path. Not exit from collapsing systems but transformation through patient rebuilding from the ground up.

This work is unglamorous and slow. Restoring a watershed takes decades. Building trust across difference requires years of shared labor. Creating functioning governance demands countless meetings, conflicts, and reconciliations. There is no app for regenerating soil, no platform for rebuilding social fabric. The work happens through hands in earth, faces across tables, seasons of planting and harvest.

Yet this slowness is its strength. Bioregional networks build resilience through redundancy, wisdom through practice, and legitimacy through service. As Bayo Akomolafe says "the times are urgent; let us slow down" — our dire circumstances require a recognition that regenerative transformation cannot be rushed. While venture capitalists seek exponential returns and politicians promise quick fixes, bioregional practitioners engage in multi-generational repair.

The choice before us is not whether to be collapse-aware but how to respond to that awareness. We can retreat into individual preparation, escape into digital abstraction, or engage in the difficult work of collective regeneration. Bioregionalism offers one path — not the only path but a necessary one. It grounds resistance in place, builds alternative from below, and creates possibility for human communities to survive and even thrive through the long emergency ahead.

The bioregional movement doesn't promise salvation. The sixth extinction continues. Climate chaos accelerates. Institutions fail faster than alternatives emerge. Yet in specific places, communities are learning to govern themselves, restore ecosystems, and create lives worth living amid breakdown. These are seeds of possibility in dark times — not enough to prevent catastrophe but perhaps enough to carry something beautiful through to whatever comes after.

Benjamin, I’m glad to see your voice working in parallel on these questions. You’ve highlighted well the importance of parallel societies/dual power, collapse-aware framing, civic commons culture, and post-partisan collaboration.

My own focus has been on reaching beyond those already “converted” to collapse awareness or regenerative subcultures. Through Symbiotic Culture, I begin from a spiritual foundation in the Transcendent, which provides a bridge not only for those aligned with bioregional networks but also for faith communities, civic groups, conservatives, and main street businesses and organizations that may not yet speak the language of collapse or regeneration.

I see real opportunity here. We’re both working on bioregional relocalization, though with different emphases. Your work highlights the practical, place-based dimension, while Symbiotic Culture brings in a broader place-based cultural framework—rooted in the Transcendent—that extends bioregional practice to a wider range of people and institutions not yet inside the regenerative silo.

I’d love to explore how our efforts might weave together—parallel streams converging into a more coherent cultural river.

You have been writing an extraordinary series of articles on bioregional and cosmolocal strategy dear Benjamin. I'm awed by the quality of your writing and thinking! Will definitely recommend your substack to my readers.